The Lorax

By Dr. Seuss

Illustrated by Dr. Seuss

“I meant no harm. I most truly did not. / But I had to grow bigger. So bigger I got.”

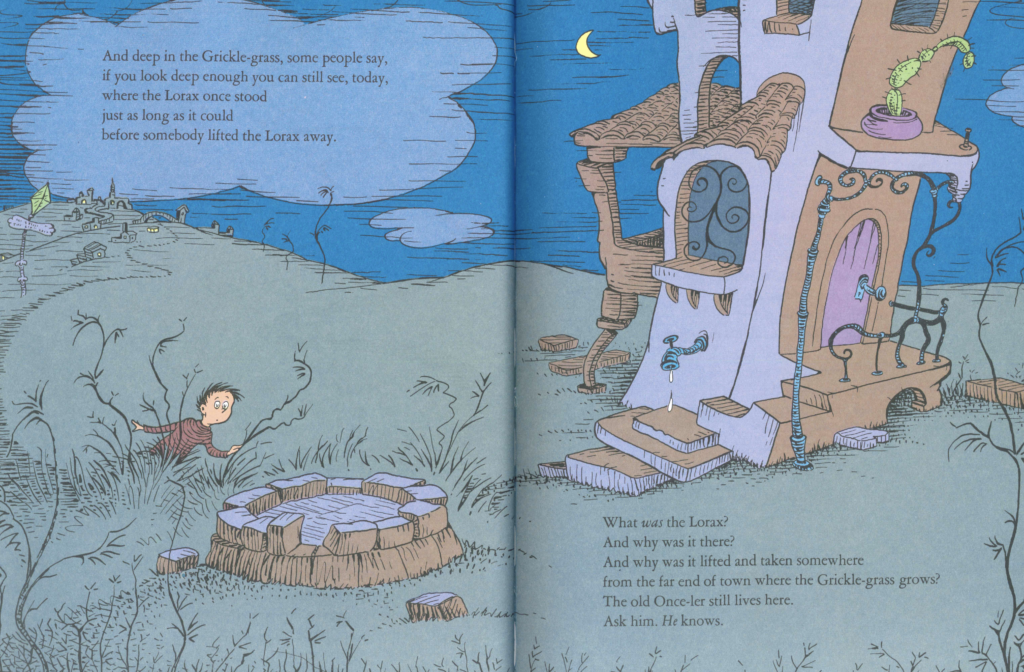

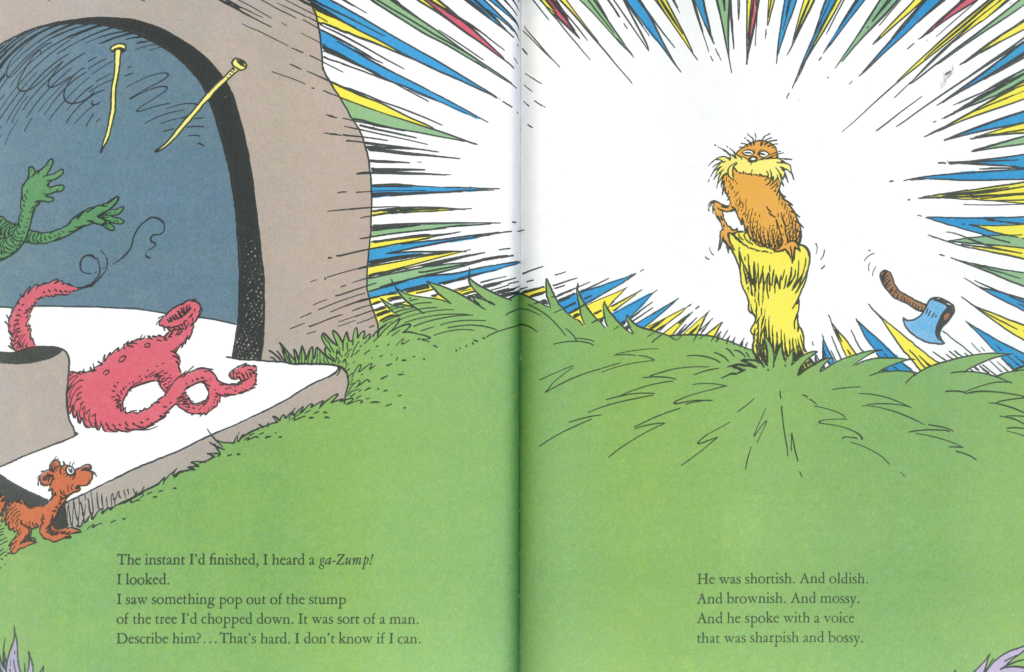

The Lorax is one of the earliest works of fantasy for young audiences to offer a warning tale of environmental destruction balanced by a call for Earth stewardship: “UNLESS someone like you / cares a whole awful lot. / nothing is going to get better. / It’s not.” The main story is that of the Once-Ler, a settler who arrives in a beautiful valley, develops business that ruins the valley’s many life forms, and then hides away in a tower-like structure to mourn the loss (see environmental destruction and human expansionism). The Once-Ler’s tale of “how the Lorax was lifted and taken away” is embedded in a framing tale in which the narrator directly addresses the audience about the mystery of the lifted Lorax—“why was it lifted and taken somewhere”. Both stories use the passive voice, which hides agency and implies that the Lorax disappeared on its own. It takes the third story, Lorax’s own voice (embedded in and mediated through Once-Ler’s memories), to help the audience realize why the Lorax was forced to leave and who drove him away. We see that the Lorax spoke for the trees and other creatures (see nature’s agency and nature’s voice) until there was nothing to speak for. This third tale reveals that what the Once-Ler sees as a “mystery” is not that mysterious at all. The climate illiterate Once-Ler continued to ignore the voice of nature until nature was killed and stopped speaking (see climate literacy). When at the end of the book the Once-Ler gives the child the last Truffula seed to plant, the message is garbled. Just how is one supposed to heed the advice of an environmental criminal, now acting like the champion of Truffula Trees he had earlier exterminated remains anyone’s guess (see deflection and greenwashing).

The Lorax is usually interpreted as urging young people to take restorative environmental action in the wake of industrial destruction (see pollution). Indeed, one of its strongest messages is that even when ecocide was not your fault, you still have a choice to enact the change you want to see (see climate activism). In our view, one underappreciated gem of The Lorax is how it can be used to illustrate the producerist nature of capitalism (see producerism). When the Once-Ler begins cutting down the Truffula trees to produce thneeds, he claims that “A Thneed’s a Fine-Something-That-All-People-Need!” Ask your students to find textual evidence about how many customers purchase thneeds and whether we hear anything about why one might need a thneed. Then look for textual evidence for how the need for thneeds is manufactured through advertising and the Once-Ler’s own claims—say, about why the factory is established and why the production must grow (see growthism). Whose needs are being met? Do we ever see happy thneed customers? Who benefits from the production of thneeds? And who pays the environmental cost? Then compare the Once-Ler’s stated environmental concerns—like “I meant no harm” and others—with his actual actions, past and present (see greenwashing). Was the Once-Ler really unaware of the destruction? Or did he choose to ignore it? How many times did the Lorax petition the Once-Ler to stop the destruction, speaking on behalf of its victims? And how many times did the Once-Ler insist that the thneeds are necessary, so the needs of the victims are small in comparison? These discussions may help students realize that the supposedly repentant Once-Ler is as hypocritical and destructive as the producerist system he stands for. When he throws the last Truffula seed to the child—because now, apparently, “Truffula Trees are what everyone needs”—the Once-Ler’s urging to plant the trees appears less a call for environmental action than the dumping of the Once-Ler’s devastation on the next generation (see slow violence). After a few reap massive financial benefits for a while, the many are left destitute in a landscape of destruction that will continue for generations. ©2021 ClimateLit (Marek Oziewicz)

For companion picturebooks about industrial pollution, see: Bill Peet’s The Wump World (1970)

See also: The Lorax (film, 2012)

Publisher: Random House, 1971

Pages: 61

ISBN: 978-0-395-31129-5

Audience: Little People (4-7)

Format: Picturebooks

Topics: Activism, Animals, Animism, Climate Migration, Colonization, Commons, Conservation, Deforestation, Ecocide, Ecosystems, Environmental Destruction, Environmental Injustice, Fish, Forests, Greenwashing, Human Expansionism, Human Impact, Industry, Kinship with Animals, Limits, Logging, Nature's Agency, Nature's Voice, Producerism, Slow Violence, Trees, Youth Climate Activism

Contributor(s):